I took my Bede BD-4C airplane up for another test flight last Sunday. It was one of those gorgeous spring days with blue skies, light winds, and nice temperature—all too rare here in St. Louis. Having had a whole day of actual spring, I am anticipating sweltering summer within the week. Missouri, you see, has twelve seasons:

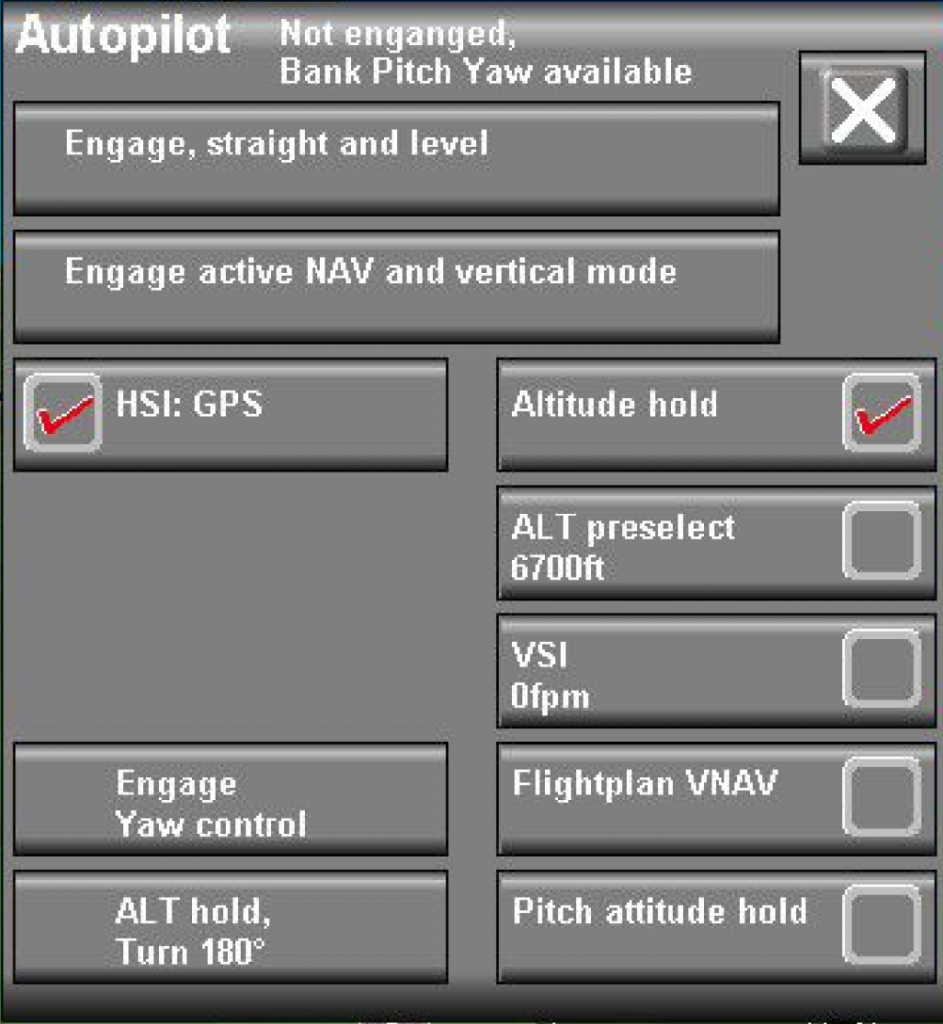

Configuring the Autopilot

Before the flight, I went through a few setup screens to configure the autopilot. I have an MGL Avionics iEFIS system. The autopilot is software built into the system. Other than the servo motors, there is nothing else to add.

When I built my Bede BD-4C airplane, I installed servos for pitch and roll.

- The pitch servo moves the horizontal stabilator. That moves the nose up and down. By controlling pitch, the autopilot can keep the airplane at a constant altitude or keep it at a steady climb/descent rate to a new altitude.

- The roll servo moves the ailerons. That moves the wings (one up and the other down). By controlling roll, the autopilot can keep the airplane flying in one direction or turn it to a new heading.

When the autopilot rolls the plane to turn to a new heading, it will also raise the nose slightly to maintain altitude, compensating for the slight loss of lift when the wings are not horizontal.

You can see pictures of the servo motors right after I installed them in my Bede BD-4C in this blog post, Final MGL Autopilot Servo Installation in Bede BD-4C Airplane

To configure the autopilot, I went through several setup screens. For each servo, I set:

- How far it could move in each direction

- How much torque it was allowed to apply

- How rapidly it should move

This sounds more complicated that it was.

To configure the pitch servo, I moved the control stick as far forward as it would go and then I tapped the button on the EFIS touchscreen for “this is full nose-down.” I repeated that for pulling the stick back and tapping “this is full nose-up.” I set the torque kind of in the middle of the range, picking 70 out of 0-100. I accepted the defaults for how rapidly the servo would move.

To configure the roll servo, I used the same procedure for establishing the limits for stick-left and stick-right. I set the torque in the middle-ish, choosing 50. For rate-of-turn, I chose 3 degrees per second, which is a “standard rate turn” of two minutes to turn a full circle. I kept the defaults for the other settings.

I turned on a “trim request indicator.” If the autopilot finds itself having to hold constant pressure on the stabilator, it puts up a “Trim” notice on the EFIS screen, along with an arrow pointing either up or down. Since my airplane does not have an electric motor to adjust the trim, I do it manually. (My role seems to have been reduced to keeping the autopilot happy.)

Flight Plan

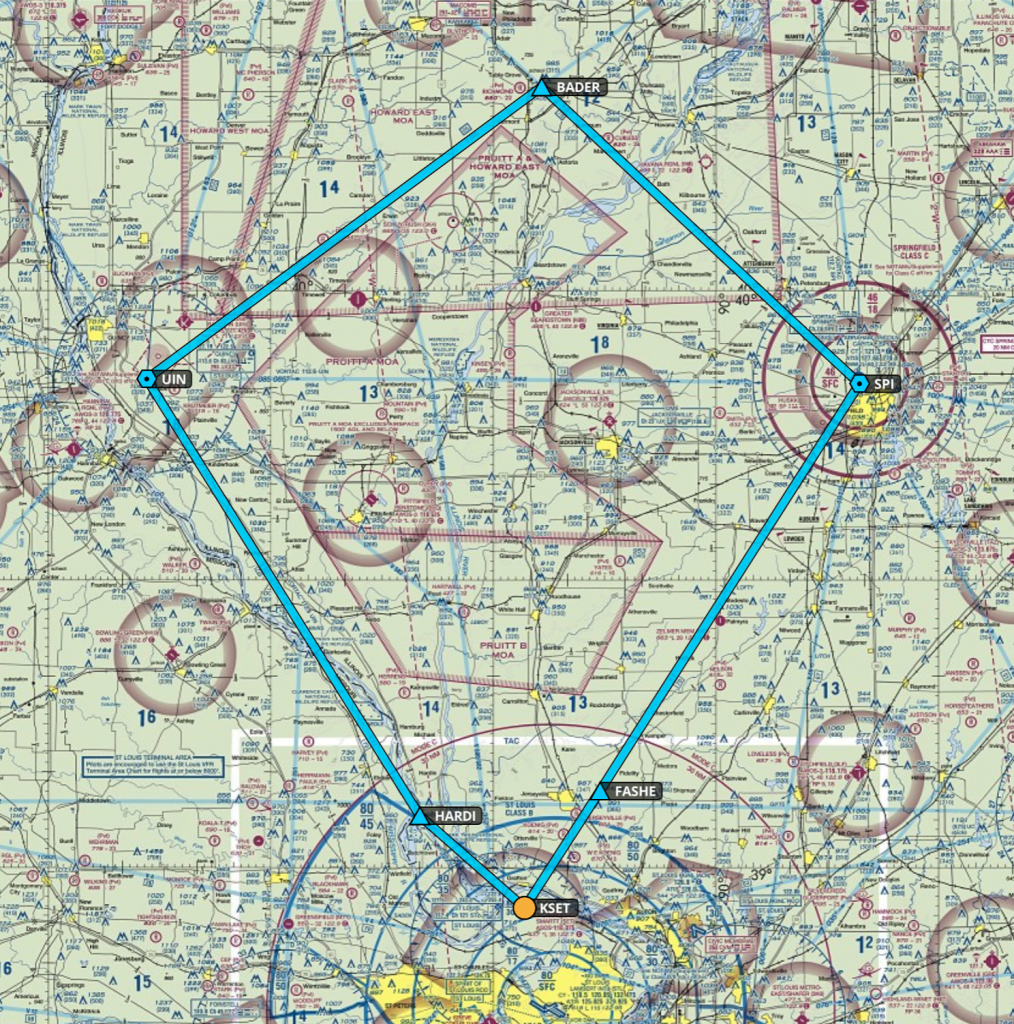

For the first time, I entered a flight plan into the MGL iEFIS with the intention of actually flying it. Like any other navigation device, you can enter the identifiers of the points along the route, pick them from the map, enter the latitude and longitude, etc. I entered the identifiers: KSET – FASHE – SPI – BADER – UIN – HARDI – KSET. In English, that is a flight from my home airport in Saint Charles, MO to Springfield, IL almost to Macomb, IL to Quincy, IL and back home. ForeFlight had forecast that this 229 mile loop would take under two hours to fly.

Test Flight

I took off and headed toward Springfield, IL at 5,500 feet. Once I had the BD-4C leveled out, I turned on the autopilot by touching the “Engage, straight and level button.” To my absolute delight, it actually worked!

I tried some of the other modes. There were several excursions away from straight and level flight, as I figured out how to properly configure the MGL EFIS so that the autopilot would do what I wanted.

On one excursion, the airplane started a tight turn to the left; I had no idea where it thought it was going so I disengaged the autopilot. There are three ways to do it.

- Grab the stick and move it in any direction. The stick is long enough that there is plenty of leverage and this is easy to do. Within a second or two, the autopilot shuts off and displays a red alert message on the EFIS screen.

- Turn off the physical AUTOPILOT power switch on the instrument panel. This instantly cuts the power to the autopilot servos.

- Disengage the autopilot via the EFIS touchscreen.

I tried all three methods. They all work. My favorite is #1; it is the easiest.

Before I reached the Springfield VOR, I had tamed the autopilot and I decided to let it handle the turn from SPI to BADER. It did so nicely, although it banked the wings more than I expected. My previous autopilots had been in my Piper Archer and my Piper Arrow airplanes and neither one would bank the wings very steeply. I am going to try reducing the bank servo turn rate from three degrees per second to two degrees per second. I think that will be less startling, especially to passengers.

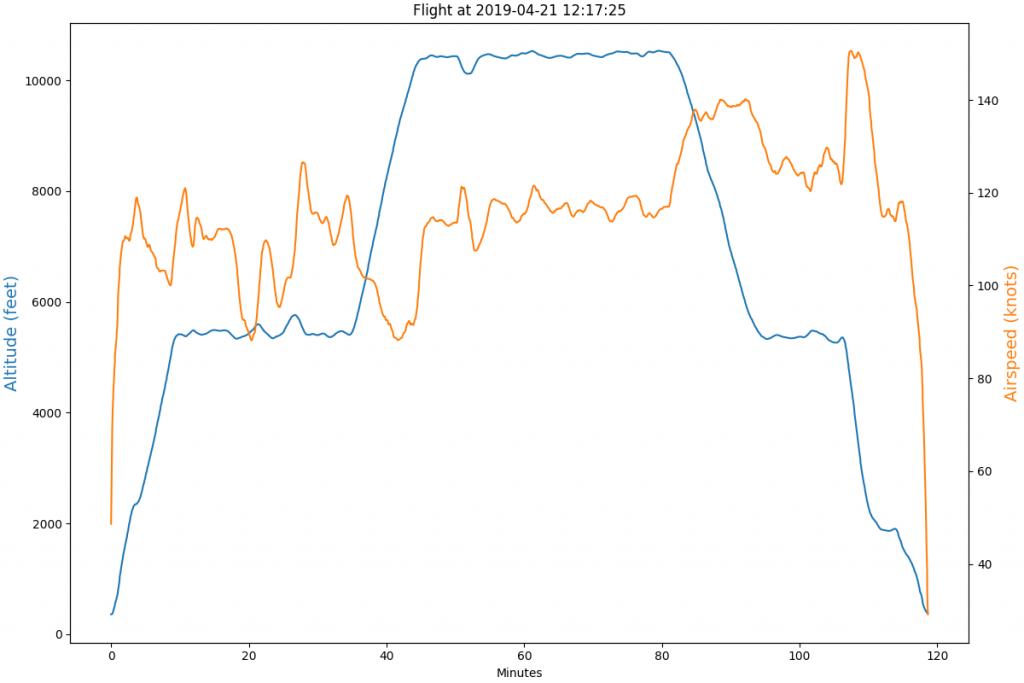

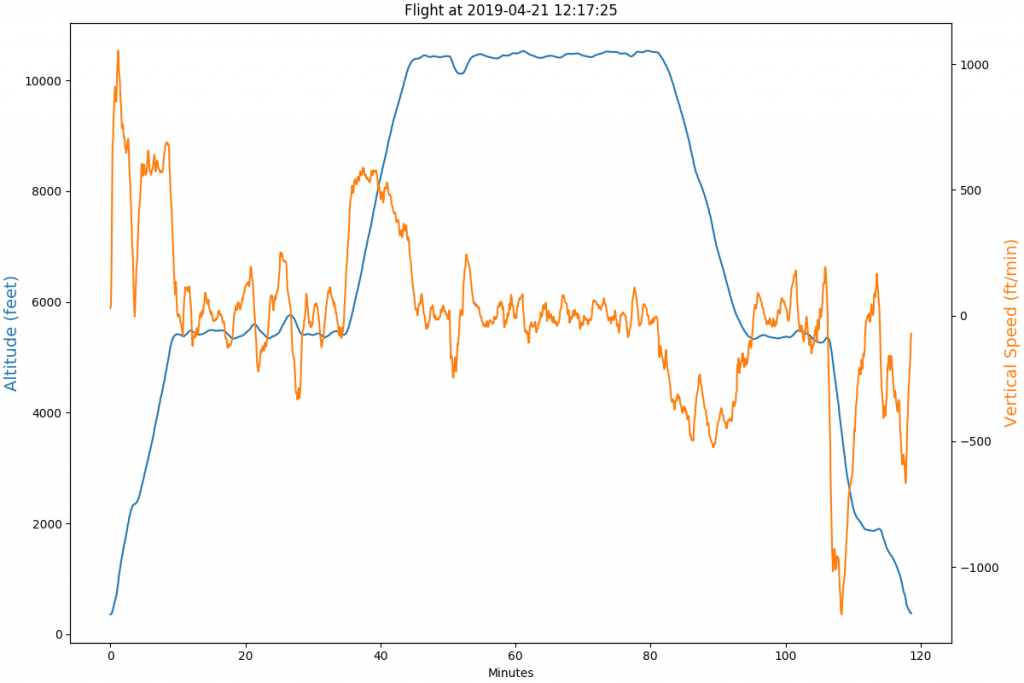

After the autopilot completed the turn toward BADER, I changed the altitude setting on the EFIS from 5,500 feet to 10,500 feet. The autopilot popped up a message requesting me to increase engine power for the climb, which I did. I also trimmed the airplane nose-up when requested.

The autopilot neatly managed the climb to 10,500 and then requested nose-down trim and a power reduction. In these graphs, you can see that the autopilot held altitude very well. I think it is kind of interesting to see the airspeed and vertical speed vary; neither of which is noticeable when you are sitting in the airplane.

Avoiding Traffic

Flying northwest from SPI, I entered the Howard East MOA (military operations area). The National Guard uses this area for mid-air refueling training. It is open for other traffic but pilots are encouraged to call air traffic control to confirm whether the MOA is “hot” or “cold.” I figured that, since it was Easter afternoon, it would be cold. Not so.

I have a Stratux ADS-B receiver in the airplane. This receives information from the FAA about other airplanes near me and displays it on ForeFlight’s map on the iPad on my kneeboard. ForeFlight showed traffic 600 feet above me and headed toward me at a high rate of speed. Although I looked for it, I could not seen the on-coming airplane. I descended and turned left to avoid the traffic. You can see the dip in altitude in the above graphs.

A few seconds later, I got to watch a tanker zip by in front of me. I sure appreciated having another set of “eyes” looking for traffic. ADS-B is not perfect but every little bit assistance helps.

Music

The last test (possibly the most important) was to crank up Spotify on the iPad. My iPad is Bluetooth paired with the audio panel in the airplane so that I can hear alerts from ForeFlight. I figured that this ought to allow me to listen to music, too.

Music worked well and the fidelity was surprisingly good. The real test, though, was confirming that the audio panel does mute the music when one of the radios “talks” to me. This means that I will not miss air traffic control talking to me.

Flight Track

I use ForeFlight for my flight planning and tracking. You can see my ForeFlight track log here.